Viewframes, Part II

To run the risk of greatly oversimplifying things, for a long time developmental psychologists held a certain assumption about the way we make sense of the world that went like this: we take in sensory data from our environment, then use our brains to order it into useful information. More recently this idea has flipped on its head. Now, a popular theory in cognitive science states that that the brains’ primary role is not to process information after it comes in through the senses, but to project its own predictive model onto the environment. This “reality tunnel" encompasses all those unconscious assumptions that together define what it is we encounter in stepping out into the world. We inhabit a waking dream.

For this conditioning to remain in the background, it needs to be arranged coherently. In the first portion of this essay, I suggested that frames do a lot of this work. More subtle than frames are the notion of images, (see related: ‘imitate’, ‘imagine’) which I use in the lineage of James Hillman to mean particular inhabitable fantasies that spring forth from the human psyche. To take the mundis imaginalis seriously is to acknowledge the nature of psyche as image, of imagination as a shimmering gate through which meaning flows. To perceive and to imagine are two sides of the same coin.

Genesis 1:27: “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them.”

2 Corinthians 3:18: “But we all with unveiled face, beholding and reflecting like a mirror the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from glory to glory, even as from the Lord Spirit.”

The imaginal in action: here, Christianity’s imago dei echoes the Greek notions of theophany (the shining forth, the shining through, the manifestation of God, of divinity) and cosmopoeisis (the creative act, the incantation, the poetry that orders the cosmos). Declaring mankind to be made in the image of the divine says nothing about how one or the other actually appears, pointing instead towards the ongoing dialogue between creator and witness.

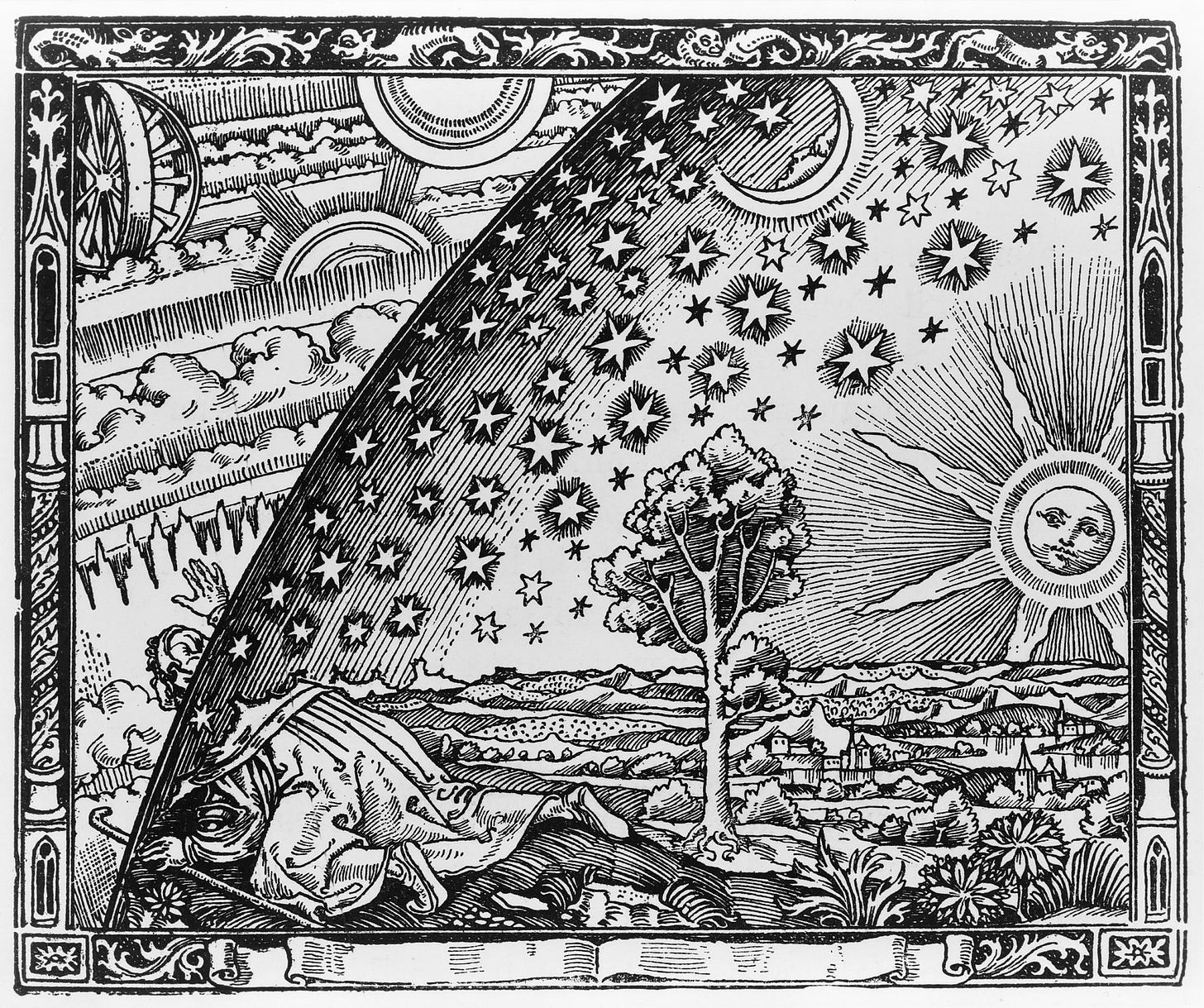

A traveler peers beyond the firmament in the Flammarion engraving.

An image is a message, one with which we can develop certain relationships, postures or sensitivities. In the words of Rob Burbea:

If we talk about self-images and the way self can be imaged, I could say, speaking a soul-truth if you like, ‘I am a lover. I am a mystic. I am a scholar. I am a preacher. I’m a theoretical physicist. I am a political revolutionary. I am a wild sexual beast who is definitely not monogamous. I am a researcher into consciousness. I am a jazz musician. I’m a crazy poet. I’m a serious composer. I’m just an ordinary guy. I’m a teacher. I’m a student. I’m a monk. I’m a clown. I’m a vampire. I’m a wild man. I’m a werewolf. I’m a healer and a shaman. I’m some kind of fugitive, some eternal wanderer, outcast. I’m the tramp on the outskirts of town. I’m a lone soldier in a forever war.

Some of those I am or have been in my life conventionally. Some conventionally. All of them mythically. None of them really.

-Rob Burbea, Theatre of the Selves

It seems obvious that the premodern mind had much more direct contact with the imaginal. It was only a couple of hundred years ago that the great majority of humanity inhabited a world filled with demons, angels, spirits and other apparitions whose reality was as apparent as anything else. It would be easy for us to attribute this stance to some childlike naïveté from which science has long since liberated the modern mind. At the same time, by limiting the range of what is real to what can be empirically calculated, modernity has flattened our ability to identify which mythic images are playing out in our lives. The hero, the martyr, the loser, the itinerant, the devotee, the rebel: if an image moves us, why insist on its unreality?

I want to conclude by exploring an image that has touched me personally. For many years, I carried intense feelings of restlessness. Why did I take this particular form? What were the gifts I could offer the world? Where was I moving towards? Throughout this time, I relied upon music as a realm of retreat and source of inspiration.

I discovered Austin Texas Mental Hospital, Pt. 3 by Stars of the Lid in late 2020, a time in which these feelings of exasperation were reaching a boiling point. The track is six minutes long and is composed of a repeated swell of watery string drones. The only movement in the track is a deep, shuddering cellolike tone that exhales every ten seconds or so, coupled with gentle pans that remind me of a plane flying overhead, or of a distant highway overpass.

The texture of the piece, coupled with the title, conjured a vivid image of a patient in some forlorn hospital ward. Beset with some condition, troubled and scared, unable to sleep, the patient gazes hazily out their window in equal parts grief and confusion. Within this spiritual exhaustion is a marveling disbelief at their situation. “How did I get here?” they wonder.

Out in the hallway or out in the building grounds, the patient’s loved one sits quietly on a bench. They are helpless and alone and don’t quite know what to do with themselves. Yet in their desperation is resolve. They sense their abdomen softly expanding and contracting in the half light, matching in its own way the traffic sifting across the city beyond. The hospital visitor knows in this moment that somehow being there is an act of grace.

I see myself laying on the bed, wracked with pain, wondering what will become of me, and also as the poised visitor. What it means I cannot say. But I know that to revisit an image, to flesh it out, honor it, ask questions of it, is a good thing to do for me, for now.